The Field Vole Cycle

With Field Voles constituting such a relatively large proportion of the diet it’s clearly important to know a little bit about them and how changes in vole populations affect Barn Owls.

One of the main characteristics of Field Vole populations is their annual fluctuation in numbers, commonly referred to as the ‘vole cycle’. Typically, numbers build over a 2-to-4-year period, culminating in a peak year, followed by a crash. One or two recovery years later there’s another peak, then a crash, and the cycle is repeated. It’s worth pointing out that differences in vole abundance can occur at relatively small spatial scales. As one area experiences an increase in vole numbers so an adjoining area may see a decrease.

There are a number of theories as to why this occurs but little consensus as to the direct causes. Where there is some agreement is in the geographical differences in amplitude, or extent, of this cyclicity; in the UK it appears to be far more pronounced at more northerly latitudes, with evidence for a cycle in lowland England currently unclear.

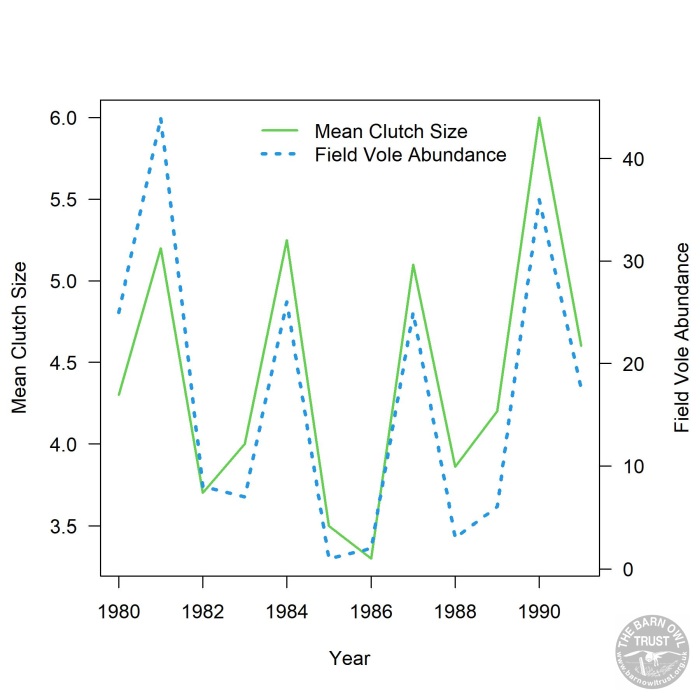

For example, in his southwest Scotland study area, Iain Taylor found a clear 3-year vole cycle which was very closely linked to both Barn Owl productivity and survival. In years when vole abundance was high, average Barn Owl clutch sizes were closely correlated and in near synchrony.

Similarly, in years of high vole abundance adult Barn Owl mortality rates were lower, whilst in poor vole years mortality rates increased.

Annual average clutch size and Field Vole abundance. Redrawn from “Barn Owls: Predator-prey Relationships and Conservation” (Taylor, 1994, p. 163)

Annual mortality rate and Field Vole abundance. Redrawn from “Barn Owls: Predator-prey Relationships and Conservation” (Taylor, 1994, p. 210)

Relationship between nesting occupancy and brood size. Redrawn from Lewis (2014), Imber Conservation Group Annual Report 2014

However, on the Salisbury Plain in southern England the work of Major Nigel Lewis appeared to demonstrate no apparent cyclicity in Barn Owl productivity. Within variation in brood sizes there appeared to be no 3-4 year cycle of peaks and crashes. Rather, there was relative stability for 3 years, followed by alternate peaks and crashes over 4 years, followed by another period of relative stability.

Of course, the picture is complicated, and Field Voles are not the only small mammal species in the UK undergoing independent, annual fluctuations in population. Taylor (1994) also found cyclicity in the Common Shrew for example. The other major prey species is the Wood Mouse, whose abundance is strongly influenced by woodland seed crop size. By necessity, decreases in the proportion of one prey species in a Barn Owl’s diet may in part be compensated for by increases in another.

In fact, there are numerous other factors at play affecting Barn Owl productivity and survival so just because one pair fails to raise any young does not necessarily mean it’s a poor vole year. However, what we can say for sure is that if there was a greater amount of small mammal habitat in the UK, particularly vole-rich rough grassland, then there would be more prey.